There is a famous character in Little Britain called Carole Beer, a computer operator who famously responds to reasonable customer requests with the phrase:

“Computer says no”

This captured something funny and true about our relationship with computers…a tendency to blindly believe whatever they say, and to allow this to override our own intuition (and in Carole’s case, humanity).

I was reminded of this when I watched Mr Bates vs The Post Office, a brilliant series made by one of my clients, ITV.

The Post Office scandal is one of the biggest ever scandals in the UK, where hundreds of sub-postmasters were incorrectly convicted of theft and false accounting, based on the output of a new computer system.

When sub-postmasters recorded financial shortfalls in the new system, people believed the system rather than the humans.

The blank, unquestioning faith in computers destroyed lives and led to despair, bankruptcy and suicide.

Only the scepticism and courage of a handful of people stood in the way.

One, Alan Bates, refused to accept that the computer was correct and instead trusted his instincts that something was amiss with the computers.

He was right.

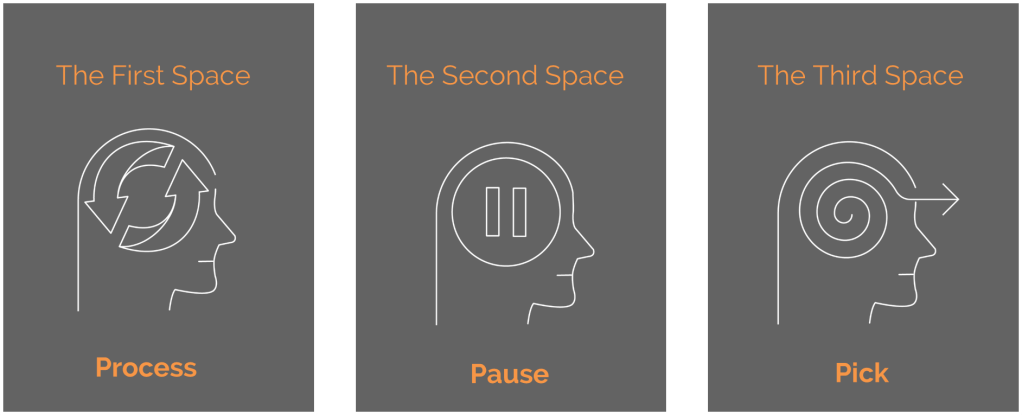

Learning scepticism of thoughts

In ACT we are taught to treat our own thoughts and emotions with a degree of scepticism.

We learn to see our thoughts not as ‘the truth’ but rather as hypotheses to be evaluated by whether they are helpful or not.

If we were to act as though these thoughts were true, what would that lead?

Could other perspectives or explanations be possible?

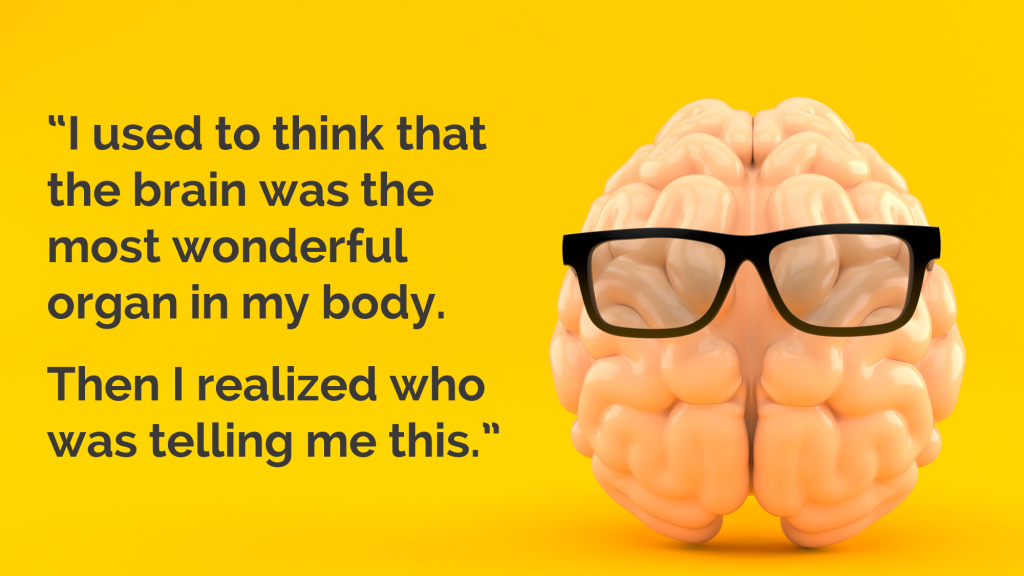

It’s like the famous Emo Phillips line:

Learning this scepticism of our thoughts can be liberating, as we learn that we don’t have to do everything our minds tell us to do.

Learning scepticism of technology

It occurs to me that we need to learn this scepticism when it comes to using technology.

We should be teaching people that outputs of technology are products of humanity, and so are flawed, limited, biased and frequently, plain wrong.

In this era of AI, algorithms, quantified selves and deep fakes, it is even more urgent to treat all outputs of technology with a degree of scepticism.

The alternative is a world where we place blind faith in technology, and where we no longer trust our own instincts.

The very definition of inhumanity. I for one say ‘no’ to that.