When you feel judgemental about yourself, do you also feel more judgemental about others? Or are you one of those people who speaks harshly to yourself in ways that you would never dare or care to speak to another? What do you think is the relationship between self-compassion and compassion towards others?

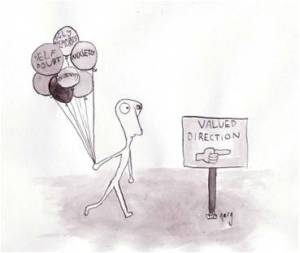

These questions matter a lot. A strong relationship between self-compassion and compassion perhaps suggests common learning histories for the two behaviours. While ACT directly cultivates self-compassion through acceptance, it emphasises other-related compassion only indirectly. If we want to improve the ways we relate to one another in organisations and daily life, we need to know how and if changing our relationship to ourselves changes our relationship to others.

The evidence is mixed. Some research suggests we treat people very differently to ourselves, while other research suggests commonalities. Looking carefully at the differences between these studies may help us learn more about what is going on.

Evidence compassion towards self and others might be unrelated

There might be no relationship between self-compassion and other-directed compassion. As children, we learn to distinguish between “I” and “you”, and much of our early sociolinguistic experience teaches us that others have different perspectives, preferences,  traits and experiences to ourselves (McHugh & Stewart, 2012). We can learn to behave quite differently towards ourselves than we do towards others.

traits and experiences to ourselves (McHugh & Stewart, 2012). We can learn to behave quite differently towards ourselves than we do towards others.

Language can create powerful differences between how we behave towards ourselves and others. One example is the fundamental attribution error where, when someone acts badly, we overestimate the effect of personal characteristics and underestimate the effects of the situation as a cause of their behaviour. Towards ourselves we are more likely to take account or circumstances influencing our behaviour. For example, while we are quite happy to blame bad driving on someone else’s incompetence or malice, we are more likely to see our own poor driving as the result of situational factors like being late for work. This is a clear case where we behave quite differently in our judgements towards self and others.

Once we make an appraisal that a person is personally responsible for the situation in which they find themselves, we are less likely to experience empathic concern and more likely to experience non-compassionate emotions such as anger (Atkins & Parker, 2012). And of course in Australia we have seen how it is perfectly acceptable to treat asylum seekers arriving on boats with their children in a very different way to how we would expect ourselves and our children to be treated. The more we see the other as different to ourselves, the less likely we are to extend compassion towards them (Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010).

Society reinforces big differences between compassion towards self and others. It wasn’t that long ago that our society seemed to reinforce young women in particular for being kind to everyone except themselves. Many older women in particular seem to feel badly about themselves unless they place others’ needs ahead of their own. So, if the distinction between self and other is seen as real, and the right social reinforcers are in place, it is entirely possible that self-compassion and other-directed compassion could be quite unrelated.

Evidence compassion towards self and others might be related

But, perhaps fortunately, there is also a growing body of evidence that emphasises the similarities between the ways we relate to ourselves and others. Many of the psychological approaches developed during the 50’s and 60’s relied upon the assumption that self-acceptance was related to acceptance of others (Williams & Lynn, 2010). More recently researchers have begun to test this idea empirically. Neff and Pommier (2013) recently found that self-compassion is positively related to compassion towards others.

Neff and Pommier (2013) studied three groups: college undergraduates, community adults and meditators. They measured both self-compassion and different aspects of other-focused concern such as perspective taking, forgiveness, compassion, empathy and altruism. Overall there was a significant positive relationship between self-compassion and other-focused concern.

Why might self-compassion and other-compassion be related?

Why did this relationship occur? The factors that were consistently related to self-compassion across all groups were perspective taking, forgiveness and the capacity to manage personal distress. Perhaps our capacity to stay present to our own difficult experiences helps us to stay present to the difficult experiences of others. Or perhaps our capacity to stand back and see our self-critical thoughts as thoughts and not necessarily the truth, is exactly the same skill as our capacity to stand back from our automatic stereotypes and judgements about others. Perhaps learning to accept our own failings teaches us that we are all fallible. Or perhaps we acquire a deeper knowing that we are not, after all, ever separate from others, that we are all “caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny” (Martin Luther King in his letter from Birmingham Jail).

However, Neff and Pommier’s study also revealed interesting differences in the strength of the relationships for different groups.

- For meditators, there was a stronger link between self-compassion and other-focused concern – perhaps we can explicitly train people to break down barriers between self and others?

- For women, there was a weaker link. Women are more likely to display higher levels of other-focused concern than men, but they are not more likely to display higher levels of self-compassion. Perhaps that social training of young girls that I mentioned earlier is still alive and well.

- Finally younger adults showed weaker links between compassion for self and others. Neff and Pommier argued that this might have been because young adults over-estimate their distinctiveness from others and they are still forming their own identities and understandings of others.

Neff and Pommier’s study has big limitations. It ignores individual differences and relies upon self-report measures. We cannot tell whether the relationship between self-compassion and compassion for others really is weaker for women or whether this is just an artefact of women feeling more pressured to self-report compassion towards others. What we really need are within-person studies using measures of behaviour and context. Am I more likely to act compassionately towards others in circumstances that have primed me to act compassionately towards myself: e.g. when I have just meditated or been treated kindly by another?

And what life experiences strengthen or break down the distinction between self and other? ACT is one experience that can build both self-compassion and compassion for others (Atkins & Parker, 2012). Perhaps other life experiences work the other way.

As I have been writing this blog, I have been working with legal educators to design programs to enhance well-being and relationships among legal students and practitioners. In emphasising objectivity and the distinction between right and wrong, legal training seems to sometimes create almost impenetrable walls between thoughts and feelings, and between self and others. And legal students and practitioners are among the unhappiest people in Western society (e.g. Kelk, Luscombe, Medlow, & Hickie, 2009). Could lawyers perhaps be a canary in the coal mine for what happens when we let language excessively dominate our lived experience and we build the walls too high between ourselves and others?

As I have been writing this blog, I have been working with legal educators to design programs to enhance well-being and relationships among legal students and practitioners. In emphasising objectivity and the distinction between right and wrong, legal training seems to sometimes create almost impenetrable walls between thoughts and feelings, and between self and others. And legal students and practitioners are among the unhappiest people in Western society (e.g. Kelk, Luscombe, Medlow, & Hickie, 2009). Could lawyers perhaps be a canary in the coal mine for what happens when we let language excessively dominate our lived experience and we build the walls too high between ourselves and others?

Relational Frame Theory offers a very useful way of understanding what is going on here. Consider the two sentences:

- I am less deserving

- I am more deserving

The first thought might precede a lack of self-compassion, while the second might precede a lack of compassion towards another. What is going on in these sentences? Our society generally focuses on the comparison words MORE or LESS, and so we have endless debates about who is more or less deserving of compassion. But by focusing on this comparison we ignore the more fundamental move contained in these sentences. The shared “I am” slips by unnoticed. It is in these little words that the “truth” gets established that there is a separate “I” that has inherent qualities. And of course what these sentences really mean is “I am more or less deserving THAN YOU” so in making the claim that I have certain qualities I am implicitly and always making the simultaneous claim that YOU are separate and have certain qualities as well.

Difference and separation arise in language. We relate to ourselves and others differently only when we are caught up in the world of words, judgments and abstractions. Perhaps Neff and Pommier’s results point to what is left when the language of separation loses its hold just a little. In those moments we see that these divisions only exist in language not in the underlying reality. In the end we are drops of water, or bubbles rising in a pot. What looks like difference and separation is really only a temporary expression of an unfolding process – and “I am” and “you are” become simply “IS”.

Difference and separation arise in language. We relate to ourselves and others differently only when we are caught up in the world of words, judgments and abstractions. Perhaps Neff and Pommier’s results point to what is left when the language of separation loses its hold just a little. In those moments we see that these divisions only exist in language not in the underlying reality. In the end we are drops of water, or bubbles rising in a pot. What looks like difference and separation is really only a temporary expression of an unfolding process – and “I am” and “you are” become simply “IS”.

Of course, philosophers through the ages have come to the same view. Rumi put it this way:

Out beyond our ideas

Of wrong doing

And right doing

There is a field.

I’ll meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass

The world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the words

You and me

Have no meaning.

– Jalaluddin Rumi

Taoism is a rich source of similar ideas. I would love to hear from you if you have other examples of similar quotes illustrating the power of language to create separation between self and other as this is an area I would like to explore further. Thank you.

References

Atkins, P. W. B., & Parker, S. K. (2012). Understanding individual compassion in organizations: the role of appraisals and psychological flexibility. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 524-546.

Goetz, J., Keltner, D., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2010). Compassion: An Evolutionary Analysis and Empirical Review. Psychological Bulletin, 136(3), 351.

Kelk, N., Luscombe, G., Medlow, S., & Hickie, I. (2009). Courting the Blues: Attitudes towards depression in Australian law students and legal practitioners: Brain & Mind Research Institute: University of Sydney.

McHugh, L., & Stewart, I. (2012). The Self and Perspective Taking: Contributions and Applications from Modern Behavioral Science: Context Press.

Neff, K. D., & Pommier, E. (2013). The Relationship between Self-compassion and Other-focused Concern among College Undergraduates, Community Adults, and Practicing Meditators. Self and Identity, 12(2), 160-176. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2011.649546

Williams, J. C., & Lynn, S. J. (2010). Acceptance: An Historical and Conceptual Review. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 30(1), 5-5.