Over Christmas I put on an additional 3kg. I have been getting rid of it ever since and I have realised that losing weight is a fantastic practice in psychological flexibility. Just about every minute of the day there are opportunities to be mindful of bodily sensations associated with hunger or satiety, and each day there are dozens of opportunities to reconnect with why losing weight is important to me.

This experience also got me thinking about why weight is such an enormous problem. Obesity rates doubled globally between 1980 and 2008. In 2008, the total annual cost of obesity in Australia, including health system costs, productivity declines and carers’ costs, was estimated at around $58 billion. In Australia 68% of men and 55% of women were overweight or obese in 2008. Part of the problem here is diminishing physical activity. The World Health Organisation reports “Globally, around 31% of adults aged 15 and over were insufficiently active in 2008 (men 28% and women 34%). Approximately 3.2 million deaths each year are attributable to insufficient physical activity.” Nobody wants to be obese but people are getting fatter, and everybody knows that they should exercise more than they do. Clearly there is a disconnect between intentions and actual behaviour.

We don’t do what we say we will do

Many studies have examined the relationship between intentions and behaviour and, somewhat surprisingly, the correlation between the two is not all that high. Have you ever had the experience of setting strong goals to exercise or eat well and then not followed through? Timothy Wilson wrote a fascinating book called “Strangers to Ourselves” outlining all the evidence for unconscious, automatic influences upon our behaviour. Meta-analyses have revealed:

“… intentions account for a weighted average of only 30% of the variance in social behavior (Armitage & Conner, 2001; Hagger et al., 2002), mainly because people with strong intentions fail to act on them (Orbell & Sheeran, 1998).” (Chatzisarantis & Hagger, 2007).

Why might this be the case? One reason people fail to act on strong intentions is because they simply forget to start the behaviour. Have you ever said something like “This week I will exercise three times” and then before you know it, the week is over and you haven’t exercised at all? This is why setting specific goals and thinking about contextual reminders is so important. In the literature, this sort of planning is called “implementation intentions”.

But another reason why people fail to act on their intentions is because their responding has become habitual and automatic. When we don’t reflect on our moment to moment behaviour we are very likely to do what we have always done in the past.

Mindfulness helps us act on our intentions

From one point of view, this might be a bit of a problem for the ACT model. If our behaviour is relatively independent of our intentions, then what is the point on getting clear on our values when we might just act out of our habits and unreflected impulses anyway? This is where mindfulness becomes really important. Values clarification on its own is of little use unless we bring awareness to what we are doing and we have the self-regulatory skills to enact new behaviours.

But is there any evidence that mindfulness can help us do what we want to do? Chatzisarantis and Hagger (2007) explored how mindfulness affects the relationship between people’s intentions to engage in vigorous physical exercise and their actual behaviour.

First they confirmed that people’s intentions to exercise didn’t actually predict whether people exercised or not. But the really interesting finding was that more mindful people were more likely to act on their intentions than those who are less mindful, even controlling for the physical exercise was already a habit for the participant. So mindful people, but not non-mindful people, were more likely to do what they said they would do! Isn’t that just the coolest reason for learning to be mindful? “Learn mindfulness and you will do what you say you will do!”

Why does mindfulness help us act on our intentions?

The authors then went on to explore reasons why mindfulness might strengthen the relationship between behaviours and intentions. Before we go any further, what do you think? Why might mindfulness increase the tendency to act on intentions?

Got something?

Perhaps mindfulness increases awareness of goals in each moment and therefore reduces the tendency to forget what we said we would do. Or perhaps mindfulness improves our self-regulatory skills so that we are more likely to be able to manage the difficult emotions that arise when we do something new or challenging. Chatzisarantis and Hagger (2007) tested a third possibility, that mindfulness helps us control counter-intentional behaviours, in this case binge drinking. They reasoned that binge-drinking probably interferes with doing vigorous physical activity (is it just me or do you too have an image of lying on a couch with a pillow over your head?), and that mindfulness might reduce the extent to which habitual binge-drinking interferes with intentions to exercise.

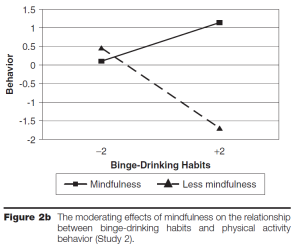

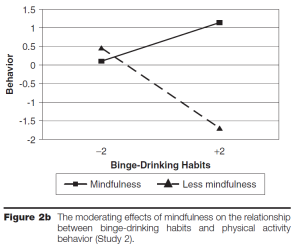

And this is what they found:

Let me step you through this diagram. Start with the dotted line first. What this says is that people who are NOT mindful and who habitually engage in binge-drinking are LESS likely to engage in physical exercise. That is, habitual binge-drinking decreases the likelihood of engaging in physical activity. So far so good, this confirms the idea that binge-drinking ain’t great for getting up in the morning and going for a run! But look at the solid line. For this group, even if they did engage in habitual binge-drinking they were still just as likely to engage in exercise as those who did not habitually binge drink. So some mindful folk still go out on the town, but they don’t let this interfere with their intentions to exercise. In the words of Chatzisarantis and Hagger (2007: 672):

“These results, therefore, corroborate the view that greater awareness of and attention to internal states and behavioral routines helps mindful individuals shield good intentions from unhealthy habits and thus can play a key role in fostering effective self-regulation. In contrast, diminished attention and awareness of counterintentional routines and habits is likely to prevent individuals acting less mindfully from engaging in effective self-regulation, as the negative relationship between habitual binge-drinking and physical exercise suggests (see Figures 2a and 2b).”

So maybe next Christmas I will be better at mindfully saying no to that Christmas pudding!