Anyone who knows me or my children will know that I am definitely both a relationship and parenting expert.

For example, before I proposed to my wife I felt I need to list all of my imperfections (which took a while), and only this morning I dealt with my two-year old’s tantrum by swearing at the top of my voice and then storming out of the room.

I’m available for paid consultancy.

However I am a reasonably enthusiastic consumer of parenting strategies and have lots of clients who are asking for ideas to help deal with the pressure of lockdown.

So here are some ideas which I like, even if the implementation for me is still a ‘work in progress’.

If you have any of your own (especially ACT-consistent ideas and resources) please let me know in the comments below.

The Executive Summary

For all you lazy layabouts who have no time to read another long winded concise and excellent post written by me, let me save you the trouble by drawing your attention to The Blessing of a Skinned Knee in which Wendy Mogel rejects the idea of making things easy for our children, of praising them constantly, of them to be somehow unique and ‘special’ – all of which loads pressure on to both them and us:

In order to flourish, children don’t need the best of everything. Instead they simply need what is good enough. This may include good enough (but dull) homework assignments, good enough (but uninspired) teachers, good enough and good enough (although bossy and shallow) friends.

Consider that “good enough” can often be best for your child, because when life is mostly ordinary…your child won’t end up with expectations that can’t be met on this worldly plane.

Or how about this little beauty:

My advice to parents is to tolerate some low-quality time. Have a little less ambition for yourself and your children. Plan nothing—disappoint your kids with your essential mediocrity and the dullness of your home. Just hang around your children and wait to see what develops.

Disappoint my kids with my essential mediocrity?

Now THAT is a parenting approach I can get behind!

Nothing I’ve read comes close to relieving the pressure on myself and my children during lockdown than this, so I urge you to read the full summary here.

Here are some more ideas:

1. You need respite

It doesn’t matter what you are doing, you need a break from it. In a study mentioned on the excellent Psychologists off the Clock podcast, soliders in the military had the lowest rates of burnout even when the break was going to war. In other words, what we need is a break from what we are doing. Do anything for too long with too little respite and we start to mentally fray. And here’s a powerful image to illustrate this point:

Ideas for implementing breaks will obviously vary but here are a few:

- Enlist others. If there is another adult in your house, work in shifts to cover short breaks. If not try to enlist a Granny to read a story or an Uncle to make your kids laugh, even 20 minutes’ respite can work wonders.

- Manage your energy. When you have brief periods when the kids are occupied, do your low-attention tasks (like admin, most emails). When you get a break from the kids, tackle high-attention tasks (like problem solving). Or just take a break and do nothing. You decide, but do one or the other.

- Deadlines work. For parents and children alike.

- Turn housework into a game. The tidy up song is good for this, but giving kids proper, grown up tasks to do on a regular basis (and rewarding this) can be an effective way of lightening the load.

- Routines are powerful because they reduce fatigue. So try to at least create a ‘shape’ to the day that everyone understands. Things like bedtime stories, a specific time for homework, meals; all of this will reduce your levels of shatteredness (technical term).

2. Beware perfectionism

We all need to lower our expectations a bit, particularly in terms of how we should be feeling and what we should be achieving. As Brene Brown says:

When we hit that wall, sometimes courage looks like scaling it or breaking through it. AND, sometimes courage is building a fort against the wall and taking a nap.

- Set small targets. You are living in a GLOBAL PANDEMIC. Survival is good! Anything extra is a distinct bonus. For example, today I changed my pants.

- Find a way of noting all your achievements (however big or small) and create meaningful ways to celebrate them.

- You cannot do it all. Think back a few months and consider what you would have advised other working parents to do during A GLOBAL PANDEMIC? What springs to mind? Let me guess, is it ‘you should definitely seize the chance to teach little Ernesto Mandarin?’

- Remember the sound of learning. From the Psychologists Off the Clock podcast, a story about a music teacher who put sign outside the music room that said: ‘This is the sound of learning’. In other words, learning is often not very smooth or beautiful, so don’t expect things to feel or sound great along the way.

3. Reframe this as a chance for your kids to learn

Before the pandemic I feel like the biggest challenge my 2 year old had faced was that time when I cut his toast in squares, when in fact he wanted soldiers.

In other words, the biggest risk for many (middle class) children is that life was too easy. Well now we can put that right!

After all, we don’t build a child’s resilience by making life perfect for them.

Let’s also remember that when we step back it gives our kids the opportunity to step up.

If we expect them to do nothing they will do precisely that. But if we expect them to step up they will do that too, and this has the bonus of building resilience and confidence.

4. Stay present

One of the reasons that burnout occurs is because we are not mentally in the present very often.

By constantly worrying about the future and ruminating over the past, we drain ourselves of energy and deprive outselves of the little fragments of joy which still appear with children in lockdown, especially if we look for them (the joy not the children).

And of course our kids notice when we’re not paying attention, when we’re scrolling on phones, when our laugh is hollow or a few milliseconds too late. Under what heading will they file that experience away?

So what percentage of the time are you present?

When I applied this question to myself I noticed that I’m often not very present and that’s usually because I was trying to avoid some kind of emotion (something called experiential avoidance).

Here is an example:

Before bed time we have the habit of watching a few short videos with both kids sitting on my knee. The videos are really tedious, so I often found myself scrolling on my phone. This has the function of relieving the boredom, but it was not exactly building joy or connection.

So now I put my phone down and try to get present to my children’s reaction. I smell their hair, fresh from bath time, and then suddenly this evening I noticed this:

I know this is a tiny example, but how much will I crave just one more of these moments once they are gone?

5. Create buffer zones

For me one of the toughest aspects of parenting in lockdown is that the small buffers between work and family interaction are squezed.

For example – and you must understand this is purely hypothetical – if I have a difficult work call and then walk out of my office straight into my 2 year old, who is asking me to be a horse, but

“NOT THAT TYPE OF HORSE DADDY NO – NOT THAT HORSE!”

Then it is fair to say that – hypothetically – I often don’t handle it well.

There is an emotional hangover with all things, and if we remove natural buffers it is inevitable that things start to go less well. At least, that’s what I’m telling my wife.

The things that work for me are:

- Trying to build a minute or two buffer before leaving the office, and tap into the type of Dad I want to be when I re-engage (i.e. loving, active, joyful); and

- Giving myself a time out if I get hijacked by my own emotions.

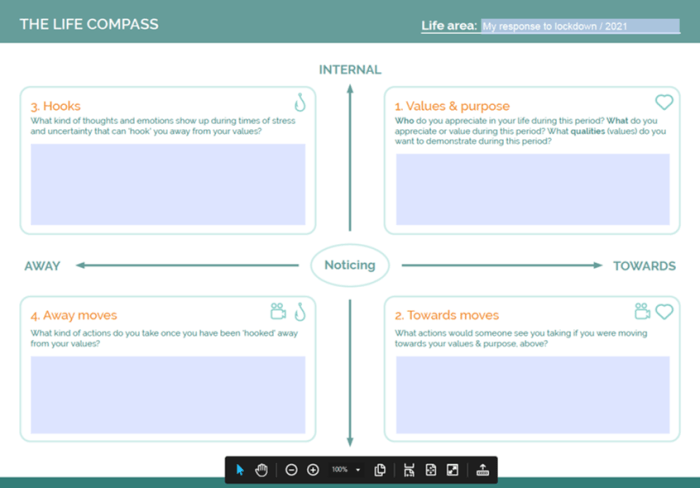

6. Connecting to values

Notice those values above: loving, active, joyful.

When I first had children I was terrified – convinced – that I would not know how to do parenting. I felt like I had no ‘Dad’ template and would really mess it up.

But actually the thing that has helped me the most is to orientate myself, again and again, to a set of values that I try to model.

It is the most enormously helpful idea for lots of reasons. Firstly, I find it impossible to eradicate the bad bits of my parenting. I’m impatient and swear too much, for example. But I am able to put positive stuff in there too. I am able to go downstairs, right this moment, and chase my children round the garden pretending to be the Coronavirus. I can tickle them until the 2 year old says

“Dop Daddy, dop!”

This moment can be all about crisis parenting, or it could be about connecting enough of these tiny moment so it becomes about something more meaningful or even joyful.

By connecting to our values, again and again, we can transform the pressure cooker of lockdown into an opportunity to connect with what matters to us most.

Further resources from actual experts

I’ve been listening to podcasts on the topic and can recommend a few here now – please see below and please let me know any that you’d add.

- Psychologists off the clock – this is a great listen but perhaps particularly for those with slightly older kids (maybe 3 – 10).

- Parenting young babies whilst self isolating and social distancing. Does what it says – good advice from The British Psychological Society (BPS).

- The BPS also has some good advice about how to talk to children during the pandemic.

- Decent advice for helping kids of all ages.

- Parenting advice for those with existing healthcare needs from Health Care Toolbox.

- Excellent advice for how to drive positive family interactions

- The view from a single parent

- Mindfulness and Acceptance Workbook for Teen Anxiety (link includes free accessories)

- Fantastic interview with Dr Jim Lucas about managing confinement with families during the pandemic

- How to talk to children https://www.smerconish.com/news/2020/4/20/how-to-talk-to-kids-during-covid-19-isolation

- This is a resource for essential workers who are struggling to support their school aged students pencilandscreen.com

Books and resources for children:

- Dave the Dog is Worried about Coronavirus. Me too Dave!

- My Hero is You (developed via a global survey of children aged 4-10 years)

- Why are our thoughts so often negative? A nice animation from ACT Auntie

- A great and free information book about explaining coronavirus to children written by a headteacher, psychologists and the illustrator of the Gruffalo